Invasive Northern Pike (Esox lucius) are a nuisance to endemic fish populations and can quickly take over waterways, but removal of Northern Pike presents a unique research opportunity. Rotenone, the chemical used to remove Northern… More

Six Mile White Water and Bluegrass Festival 2018

Pre-trip Jitters for Wrangell St. Elias National Park Expedition

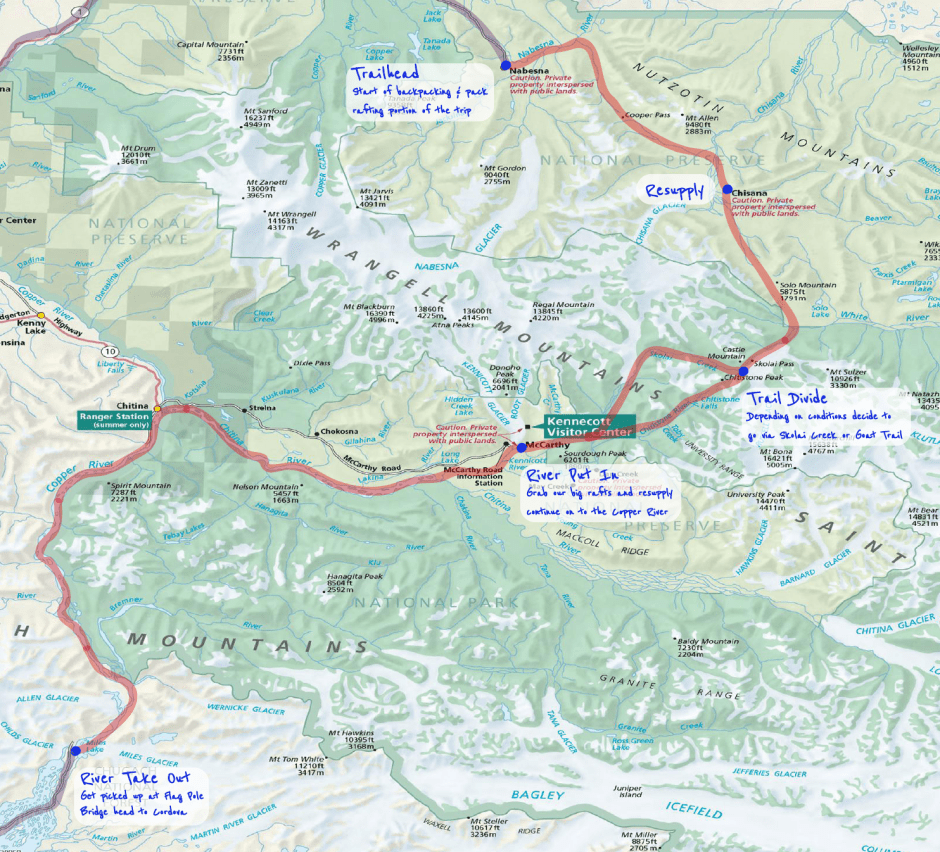

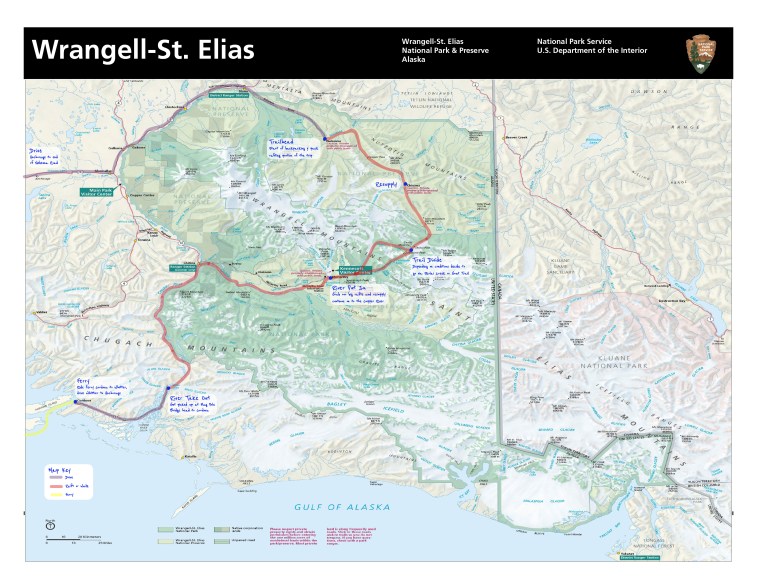

Nervous and excited energy has surrounded me for quite some time. I’m leaving for a three week journey through Wrangell St. Elias National Park in the Alaska wilderness. My group includes 14 of us who are all a part of the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Expedition class. We will be backpacking and pack rafting from the end of Nebesna Road to McCarthy through the park in just roughly under two weeks with only one resupply in Chisana along the way. Once in McCarthy we will be resupplying and picking up our large multi person paddle and oar rafts to float the Copper River south to Cordova. We will have traveled nearly 300 miles over land and water to get there from Nebesna.

I signed up for the trip back in January. My prior experience is only a number of overnight backpacking trips. The longest distance being 34 miles. I have now only pack rafted a river twice. I wonder nearly every day now if I am capable of completing this trip. Am I fit enough? Will my bad knees cooperate? What if I can’t continue on? These questions play through my mind frequently. As the trip nears I find myself trying to quiet these doubts more and often.

Oddly at the same time I feel confident and prepared to go. I have checked and rechecked my bag more times than I can count. I visit REI, the grocery store, or a hardware store every other day to get things to improve my systems, reduce weight, or make life more convenient for when I’m on the trail. I have prepared breakfast and dinner for my tent group, learning to dehydrate meals, count calories and consider weight. My DIY pack raft has been tested repeatedly for leaks and has been patched with glue. Everything gear wise and food wise is prepared.

I have also been keeping very active spending almost the entirety of all my weekends outdoors on the trails and frequently going for long evening strolls and hikes. My pack feels heavy on my back for the first mile, but then I settle into a pace and don’t notice it anymore. Maybe I can do this trip after all?

My mind also wanders to the people I won’t be able to talk to for three weeks. My mom, who I call on the phone three times a day, sometimes more, even though we live together at the moment. She is my advisor and problem solver for all things, my rock. My dog, Aspen, even though she doesn’t talk, her companionship will be missed. My brother, step dad, friends and coworkers who are all so supportive, but wonder why I’m going on this crazy trip. I will miss them all. I know they each send me well wishes on this adventure and that is reassuring.

Their encouragement also makes me feel prepared. They constantly tell me I will be fine and have so much fun. I know I will, but anxiety about the trip has been very real. I am so excited to get out there though. To disconnect from social media, life’s daily grind, and modern convenience. It will be a simple three weeks. Simple sounds nice. I feel like my soul will have a chance to recharge and reconnect deeply with the mountains and outdoors. I draw energy from being outside in Alaska.

The ominous and inviting mountain peaks, the wildlife that scurries along the ground cover, the foliage that rustles in the wind, it draws me in. I feel so alive in moments when I am surrounded by that all. I get to be surrounded by it for three weeks and I can only imagine how much energy and inspiration I will have gained by the end of the expedition. I long for how relaxed I will feel mentally by being so close with nature.

My mind is kind of a goopy mess of thoughts with the way I feel about this trip. I’m ready to go though. I hope the group joining me is too. We are embarking into the backcountry wilderness of Alaska and I couldn’t be more thrilled. So ta ta for now, I’ll be back in three weeks.

If you’re interested in tracking our progress while we are gone please visit HERE. This will begin being active when we start the trip and will update nearly every 30 minutes. Don’t worry about us all if it doesn’t though! No news is good news.

Sonar fish counts on the Chignik River

Field work is often seen as the glamorous part of science, where researchers get to experience the outdoors and be close to the subjects that they study. The sad reality is though that most scientists spend their time analyzing and processing data on computer screens at office desks. For Myra Scholze, a Fish and Wildlife Technician, for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG), this is no unfamiliar territory.

Scholze began working for the ADFG seven years ago in the sport fisheries division in Kodiak. Two years ago, she began doing research for ADFG near Chignik, Alaska on the Alaskan Peninsula. The community of Chignik is primarily a fishing village that relies on the commercial and subsistence fisheries there.

Scholze’s work with ADFG helps manage those fisheries to maintain their sustainability. Her work is to count the salmon that swim up river between May and September.

“Counting the fish is what tells fish and game when to open and close commercial fisheries,” Scholze said. “For each day of the month, in June and July, there’s escapement goals you’re supposed to meet that indicate that you’re going to meet your total number of fish that’s needed to maintain a sustainable run. We count the fish up and meet those goals then the manager at Chignik decides when and what areas to open and for how long.”

Specifically, Scholze is funded through a grant that is comparing and trying to find the correlation between fish counts made on a weir or on a sonar. The two fish counting methods generate a massive amount of data that must be processed.

Weir measurements are made by forcing salmon through a bottleneck in the river, the weir itself, and recording video of the salmon as they pass by. Researchers then go back and count how many individual salmon pass the camera lens.

Sonar doesn’t record video in a traditional sense, but rather records how sound moves through water. Sonar data is collected on both banks of the river and then a researcher must sit and watch back each of the videos and count how many fish blips they see on screen.

“We have two sonars and every ten minutes they create a file that looks kind of like a fish finder on a boat. That’s what you’re counting,” said Scholze. “Every bank creates 144 files per day, we have a sonar on each bank of the river, so we are creating 288 files a day. Over a month you’re creating about 10,000 files and that’s why we have such a back log and why I count files.”

The massive amount of data and the nearly real-time nature (the videos can be sped up slightly when only a few fish are moving by) of watching back the files and counting fish makes for long work hours. Scholze has spent months outside of Chignik in the Kodiak ADFG office, in addition to long evenings at the bunkhouse in Chignik, just counting back fish on videos, so finding a correlation between weir and sonar counts may take years to come. The preliminary conclusions about correlation can’t even be made yet.

“They’ve looked at it [the correlation], but we don’t have enough done from 2016 yet.” Scholze said.

The work may be grueling to some, but to Scholze she loves being able to collect the data that helps inform management decisions for Alaskan fisheries. She intends to continue working for ADFG in Chignik for as long as they have files for her to count. She’s currently in Dutch Harbor, Alaska working for ADFG as a Fish and Wildlife Technician for the crab fishery there. Myra will return to Kodiak in the spring to restart her sonar counts before heading back to the field in Chignik as a Fishery Biologist.

Stickleback – The super fish

Darting through Cheney Lake in Anchorage, Alaska are thousands of small fish, about three inches in length, with three spiny projections that jut off the top of their bodies, pricking anything that dares touch them. The color of their scales varying in color depending on the season, sex, or population from which they descend. They gleam shiny silver, blue, or a dull brown, sometimes with a greenish hue. They’re named threespine stickleback, and they’ve become a powerhouse organism for study. Found in nearly all Alaskan lakes and across most of the northern hemisphere, scientists have taken keen interest in these fish for the practical uses they hold for studying evolution and conducting research.

At the University of Alaska Anchorage, Kat Milligan-Myhre, heads a laboratory of undergraduates, graduates, lab techs, and post docs who are all using threespine stickleback as a model organism for a variety of projects on host gut microbe interactions. The lab is able to study how the microbes within the gut of threespine stickleback, the host, affect a variety of things like development, physiology, behavior, and more. Milligan-Myhre developed a procedure that allows the lab to fertilize eggs of the fish and then make them free of all microbes. They can then add back in select microbes or none at all to study how the microbes are actually affecting the fish.

“Stickleback have a number of really cool qualities. One is that they are transparent so we can actually watch fluorescent microbes move around in the gut of a live stickleback,” said Milligan-Myhre, “We can make large amounts of genetically similar eggs from a single cross or a couple of crosses… with fish you can get 100 to up to 200, if you’re lucky, of genetically related fish. That allows us to have a lot of power so we can do some really good statistical analysis on these changes that we’re seeing when we treat these animals.”

They are studying a variety of populations from varying lakes across Alaska, but by far their most frequented lake of interest is Cheney Lake. The lake had threespine stickleback introduced to it in 2009 from a parental population found in Rabbit Slough, Alaska, by Frank Von Hippel, a former professor at UAA, who like Milligan-Myhre used them as a model organism. Von Hippel’s lab was interested primarily in the evolution of the fish, however.

“What really sets stickleback apart from zebrafish, which are the traditional go to fish model, is that we can take stickleback that have evolved in different environments and we can relate the environments in which they evolved to their physiological and genetic variation,” said Emily Lescak, former doctoral student of Von Hippel’s, currently working as a post-doctoral fellow in Milligan-Myhre’s lab, “Basically we can understand what selection pressures in the environment cause a fish to evolve in certain ways, so we can understand what sort of ecological pressures there are on fish populations.”

Incidentally there’s already evidence that the threespine stickleback Von Hippel introduced into Cheney Lake are already undergoing evolution from their anadromous (meaning the fish, like salmon, are born in freshwater, travel to the ocean, and then come back to the freshwater to mate) ancestral form, to freshwater forms. The threespine stickleback in Cheney Lake were introduced in 2009 after the Alaska Department of Fish and Game applied a Rotenone treatment in October, 2008, to the lake. Rotenone was used to eliminate northern pike that were introduced illegally. The Rotenone treatment wiped out all fish populations in the lake and allowed Fish and Game to restock Cheney Lake with rainbow trout, and Von Hippel to introduce threespine stickleback from a known population, Rabbit Slough. Milligan-Myhre’s lab has been collecting data on Cheney Lake and threespine stickleback from the lake monthly to assess the changes of the threespine stickleback population over time.

“We can follow evolution in real time. That’s exciting,” said Milligan-Myhre.

The lab is collaborating with a lab at Stony Brook University in New York to look at genetic differences as the population evolves. Milligan-Myhre’s lab hopes to also take a look at how as the population changes over time into their freshwater form the microbiota and threespine stickleback’s immune response to microbes also change.

The tools these fish offer are nearly limitless from using them as a model for biomedical research, as they have similar physiology to humans, to studying evolution, these fish also make great models for studying ecotoxicology, as well as, host microbe interactions, just to touch on a few of their benefits. The threespine stickleback came to be a model organism in the 1900s with the work of Nobel Prize laureates, Niko Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz, and Karl von Frisch, because of the ease to which they could be manipulated in the lab, now in 2017 the threespine stickleback shows no signs of slowing down as being the model organism of many scientist’s dreams. In 2018, hundreds of researchers will even gather together for the 9th International Conference on Stickleback Behavior and Evolution in Kyoto, Japan. These prickly little fish may not seem like much to the majority of people, but to many scientists they are the crux of their entire careers.

Written by Kelly Ireland. Kelly Ireland is an undergraduate student doing research in Kat Milligan-Myhre’s lab.

South Fork Eagle River

Took a short hike out at South Fork Eagle River the other day. The scenery was absolutely unreal.

There’s something fresh about fall.

I don’t know if it’s me or the air.

Maybe it’s because I feel like I’m about to fall –

Or if my hearts in snare.

The air has a crispness

Like the feeling of change.

Kenai Dipnetting

There are some things that only Alaskans will ever understand and one of those things is dipnetting. Every year the Alaska Department of Fish and Game opens up about a 2 week dipnetting season for reds on the Kenai River. Take a look around the office at work and there seems to be a sudden lack of people once ADFG announces the opening of the season. I’ve lived in Alaska for six years and this year was the first time I’ve gotten to experience dipnetting for myself.

Dipnetting was not at all what I expected to say the least. We drove down late Friday night despite the fact I had called in sick that day with a fever that hadn’t subsided. We set up camp at the Beluga Lookout RV & Campground, which sits on the bluff of the north shore of the Kenai River, at around 11 p.m. Going to bed around 1 a.m. we got a few hours of sleep and quickly gathered up our stuff and drug it down the trail to the beach. Pulling on the waders I made my way into the water with the hundreds of other crazy Alaskans who were there long before the day of fishing opened at 6 a.m.

It wasn’t long before I saw just how serious people were about catching their fish. Five minutes into being in the water some guy yelled at my friend and I for how we were somehow in his way even though we had been there before him. We watched some far braver souls float down the river in wet suits and dry suits with personal floatation devices, poles in hand, and flippers on their feet as they tried to net fish in the swifter waters further from shore and the masses. I watched far crazier people with just t-shirts, shorts, and tennis shoes brave the water for hours with no waders as if they were on a tropical vacation in Hawai’i.

We didn’t catch much that day, but neither did anyone else. The commercial fishermen were out that day and it seemed like the consensus on the beach was that it was all the commercial fishermen’s fault for our bad luck at catching. I ended up with three salmon in the cooler and had brought an additional salmon ashore early in the day, but being the beginner I was, I didn’t pull it far enough ashore before it flopped around and then swam away. My friend blamed it on the fact I was too dumb to put the net over the salmon once it started to get away, but attempted to pick the slimy thing up with my hands.

We fished late into the evening and at about 7 p.m. me and my best friend called it a day and hauled all of the group’s stuff up the hill as the boys continued fishing. We had 15 salmon that first day and more gear than we could have ever needed in our cart and it was quite the task pulling it through the sand and then up the steep hill to the campground. We were probably lugging up the hill close to 100 pounds it felt like. Some random stranger helped us pull it through the sand, many others just gawked, and one pair of guys with a cart of their own passed us up while we ascended the hill. Jokingly I shouted at them they must not have caught as much fish.

Back at camp Lucy and I prepared the fire and then ate more S’mores than I’m comfortable admitting. We discussed whether Kraft, Nabisco and Hershey’s were in business together and came up with S’mores to sell more of their product as we wondered why the heck anyone in the world would want marshmallows other than for a S’more.

Soon the boys were back and they started filleting the salmon while we tended to the fire and set up everyone’s wet clothes around the fire to dry. At around 11:30 p.m. the rest of our group arrived from Anchorage. We all got to bed pretty late that night, but all agreed we were willing to get up early again the next day.

At 5:15 a.m. the next day when I was woken up I promptly regretted the decision I had made last night to get up early and requested that I sleep in instead still feeling quite sick. Falling back asleep I woke up at around 8:30 a.m. and then made my way to the beach after receiving a text from my best friend that I must bring more coolers down since they were slaying. Sure enough when I made it down there, they had already filled one cooler and were bringing in more. I quickly got in waders and made my way out into the water, but the run appeared to be over. I didn’t spend much time in the water that day and once I caught one fish I called it quits to let the boys fish for the rest of the day. Around 5 p.m. the reds started running again and Lucy and I became designated fish cleaners as the boys brought in fish after fish and we could hardly keep up. When it started to slow again around 7 p.m. we all called it quits for the day and drug our 2 coolers full of fish up the hill (Lucy and I had already lugged up one earlier that day). We prepared dinner and packed up and thus concluded our dipnetting trip that evening.

Dipnetting was definitely an experience of a lifetime getting soaked to the bone standing in the water, being sunburnt to a crisp, not showering for 3 days, and getting covered in fish slime and guts. After this first trip I definitely will be more prepared for next time, but now knowing what it’s like here’s the advice I have for other first timers:

- You’ll know when you have a salmon in your net. If you aren’t sure, you probably don’t have a fish, don’t waste your energy dragging your net to shore and risk losing your spot.

- Protect yourself against the sun. Wear sunscreen, sunglasses and a hat. If you’re like the rest of the crazies out there you’re going to be in the sun almost all day and believe me you will need these things to keep from looking as red as the salmon meat.

- Invest in neoprene gloves. Most people were wearing cheap plastic rubber gloves and complained of them leaking, I had neoprene gloves on and while my hands were always wet they were always warm. If you don’t want to spend the money on neoprene gloves wear at least something on your hands. The metal pole of the net gets pretty cold in the water.

- Dress in layers. You’ll probably be cold in the morning or when the wind picks up, but it can also be pretty hot during the height of the day when the sun is out.

- There are free hot dogs and hot chocolate on the north shore. A church mission group is out there every year handing out hot dogs and hot chocolate. Be sure to say thanks.

- Bring ready to eat food. You aren’t going to have time to go back to camp and cook up a gourmet meal so unless you have a designated cook, bring down granola bars and other ready to eat foods.

- Don’t go in as deep as your waders are high. Waves do happen at the mouth of the Kenai and boy did I regret going out to almost the top of my waders and then immediately getting soaked when the waves came in.

- Make sure your waders don’t leak before you get to the Kenai. Repair and seal any holes. There’s nothing worse than being wet in something that was supposed to keep you dry.

- Read up on fishing regulations. Information on dipnetting in the Kenai is available here.

- Bring only what you need to the beach. We had a lot of extra stuff the first day that we didn’t use at all and then had to lug up the hill at the end of the day. On the second day we only brought the essentials and that was much nicer.

- Don’t forget to drink water. I felt pretty dehydrated during the trip because I wasn’t willing to leave my fishing spot to go grab a drink of water. For other die hards you might want to invest in a camelback that you can wear with you while you’re fishing so you never have to leave the water. Now I just got to find a solution to having to using the bathroom…

- Behead, clip and gut fish on the beach. ADFG requires that all fish caught while dipnetting must have the corners of the tail fin clipped before the fish is put out of sight (i.e. into your cooler). With each fish you catch you should clip the fins and the gills (to kill the fish faster and bleed it out, make sure to cut all the way to the white part of the gills). It helps tremendously for later if you behead and gut the fish then too (you’ll be too tired to want to do it at the end of the day). Since we had more people in the group than we had waders or nets we always had 1 or 2 people ashore to do this pre-filet cleaning which allowed people to have their nets in the water for longer.

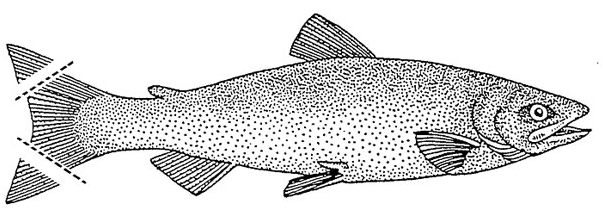

ADFG requires you clip the tail fins of salmon caught while dipnetting as shown. - There’s no such thing as too much cooler space. We filled five coolers on our trip, with just 50 fish. If each of us had limited out we would have needed more cooler space than we had.

- Be considerate of those around you. Don’t be loud, disrespectful or take up more space than you need, and be sure to clean up your space when your leave. Everyone is just trying to fill their freezers and not have to spend a bunch of money on food. Stagger nets if you have to when people get close. Just remember every Alaskan resident has just as much a claim to having their net in the water as you do and the fish are swimming sporadically anyways so chances are someone having their net in front of you isn’t going to decrease your chances of catching fish.

- Must have items for dipnetting:

- fishing license

- dipnetting permit card

- dipnet

- waders

- sunscreen

- hat

- sunglasses

- gloves

- fish bonker (a rock will do if you forget)

- filet knife

- filet knife sharpener

- scissors or gardening shears (for clipping gills and fins)

- five gallon bucket or two (for bleeding out fish after you cut their gills and for cleaning them off)

- coolers

- ice

- ready to eat food

- water

- a set of dry clothes and shoes to put on when you take off your waders

If you have any other suggestions or questions about dipnetting on the Kenai (I’m by no means an expert, it was only my first time after all) feel free to comment.

Adventures are us

By Ashleigh Roe

It’s been just over a day since I have landed on this island. Left to our own devices, Mother and I went for a walk along the beach. One of her associate trailblazers, dog entailed, joined us on the trail. The hunting began right away- the treasure has been easy to find so far. Unfortunately, the dog has also found his prey. Spitting and hissing, a sea otter backs into the rocks.

To our great chagrin, we were forced to evacuate the beach- too many intruders invading our turf. Alas, in one final effort to loot the waterfront we excavated what seems to be a radiator and piling post. A passing gent was kind enough to aid the transportation of our treasure onto the trail. The haul out was long and arduous, taking a toll on our muscular and respiratory systems. Finally, our journey had come to the end. Mother and I loaded the cargo into the back of the caravan with help from Sharon. At last we set forth to the homestead for a short refresher (and wash). From there we attempted to place an order at the local sandwich shop- they are grievously closed for a short season. Instead, we made the lengthy trip to town to dine in the local Greek eatery.

More to come. This is adventurer A.D.Roe signing out.

Vagabond ventures: Monika Fleming

Anchorage is the largest city UAA geology major Monika Fleming has ever lived in. She grew up in Chewelah, Washington where only 2,607 people reside in three square miles. Monika has climbed mountains rising, in feet, more than six times her hometown’s population. Additionally, she traveled out of the country on her own and worked in numerous national parks. Her journey through life hasn’t always been clear, but her love of the outdoors and for adventure has driven her to new and unexpected places.

Fleming grew up hiking and skiing with her family; yet it wasn’t until college that she fell in love with the outdoors. After suspension from BYU Idaho for smoking cigarettes, she started working at Yellowstone National Park in a fast food joint in Mammoth Hot Springs. There she developed a love of geology and began spending her days in the mountains around the park and, by the end of summer, was doing twenty-mile mountain summits. The free spirited culture of working in a national park took hold of Monika and gave her a “go get em” attitude for adventure.

When summer came to a close, Fleming went back to BYU Idaho for the fall trimester. Then, during winter trimester, she returned home and became a snowboard instructor at her hometown mountain, 49˚ North Resort. Another instructor and fellow BYU student, Drover, suggested Monika take a course called Spring Summit when she returned to school in the spring.

Upon spring enrollment, Monika joined Spring Summit – an 18 credit six-week outdoor management course. It was another chance for Monika to live her life to the fullest. The course included ropes courses, desert survival, backpacking, mountain biking, rafting and canyoneering. One of the most stand out experiences for Monika during the course was rafting a 46-mile portion of the Colorado River known as Cataract Canyon.

“Cataract Canyon, that’s the canyon, that has a series of 29 rapids that scarred me for life, but now I’m trying to be a raft guide because I want to not be scared. Water just freaks me out. It’s always freaked me out because it’s so powerful.”

Monika’s raft was flipped by a hole and everyone on the boat had to cling to the raft as they went through class 3 and 4 rapids before flipping it back over. Monika decided to spend the rest of the trip on the pontoon boat to avoid flipping. However, danger was not behind her.

Monika sat next to a 4 to 5-month pregnant classmate at the front of the pontoon raft. The girl wasn’t hanging on tight enough as they came over a huge rapid and was bucked off in an area called Devil’s Gut – where getting sucked in means death. Monika alone was attempting to retrieve her, screaming for help, when a guide cut the motor, pulled her in, started the motor again, and avoided imminent danger in about two seconds.

Despite the danger she and the rest of her classmates had faced Monika wasn’t willing to back down from conquering the outdoors. Following the class Monika traveled back to Yellowstone for the summer before returning to BYU Idaho for the fall semester. Her love of the outdoors shortly overcame her desire to finish school though.

“I decided that I basically had my associates degree minus four credits, but I just didn’t really want to be at BYU anymore. I had some friends from Yellowstone who were going to go work in Colorado for the winter so I just finished my semester and went down to Colorado and became a ski instructor.”

At the end of the ski season Monika decided to make her way to Glacier National Park. She worked as an employee dining room chef in Swift Current cooking meals for all her co-workers with almost no experience in a kitchen. The decision to go to Glacier was Monika’s first big leap of faith for the outdoors.

“This was the first thing I’d really done totally on my own. The school thing I did on my own, but that was with a school program. I just drove up to Montana and I was totally by myself. I’ve had friends and connections and stuff like that, but this was totally just kind of on my own.”

During her summer in Glacier National Park Monika did a lot of hikes and solo summits. She also met a guy named Samurai, who every year visits Nepal. Samurai invited Monika and two others (Shannon and Hayden) to Nepal to work in an orphanage with him at the end of the summer.

“I saved up money, I bought a plane ticket, saved up more money to live off of and then I flew to Nepal… We stayed in an orphanage for a month just on the border of India… That was like a really eye opening experience that was the pinnacle of this kind of wild crazy traveling kind of like freedom thing going on. That kind of grounded me. It put a lot of things in perspective, I’ll tell you that much. Nepal – they have nothing. They have tourism, they don’t manufacture anything, they make rice and millet and it’s sandwiched right between India and China and that’s how most of the world lives.”

Seeing poverty first hand Monika gained a greater appreciation for what she had and fueled her desire to experience more of the world. During Hayden, Shannon and Monika’s stay in Nepal they planned a trek in the Himalayas. Just one day into the trip Shannon and Hayden turned around, but Monika continued with their Nepali guide.

“We went to this place called Machapuchare base camp and it’s in the Annapurna region. That’s where most people go trekking if they go to Nepal because they have Everest base camp and Langtang National Park which is right north of Katmandu.”

Machapuchare Mountain, standing at 22,793 feet with two peaks has never once been summited. Since summiting is illegal, many climbers don’t want to climb any portions of Machapuchare. Monika is one of the few who has hiked parts of the mountain.

“There’s all this mysticism around it. No one’s summited it because there’s a god that lives up there, no one’s summited it because the mountain itself is a god, all this different stuff.”

While Monika didn’t summit the mountain she took a Feldspar heart shaped rock home with her as well as important life lessons.

“I actually broke on that trip because I was just out in the middle of the Himalayas with this guide. We were not near any tourists anymore. We were just in the Himalayas. There was people on the side of the mountain, like families, chopping wood and it was just really freaking real. The water wasn’t clean where I was at. They were boiling it, but it had chunks in it. It was really hard. It made me realize what a prissy – I mean how lucky we are.”

Spending time in Nepal brought things into perspective for Monika. Going first hand into the outdoors brought Monika back to her beginnings. In a journey with many detours she decided that pursuing geology was the path she needed to take.

“Maybe you could call it an existential crisis, but it was something, it was good. That’s what brought me here. I ended up here after that. I wanted to go back to college and I knew what I wanted to study. I wanted to go to Western Washington University, but my credits wouldn’t transfer there and I’ve always wanted to live in Alaska… I just kind of took a gamble coming here.”

Monika since Nepal, moved to Alaska in 2014 and has been attending UAA ever since as a geology major. This summer Monika plans to do some sort of guiding job, most likely rafting despite her previous experiences in Cataract Canyon. Until then Monika has been shredding the slopes of Alyeska and sneaking in outdoor recreation classes at UAA including a sea kayaking class this April.

Solitude seeker: Molly Liston

Molly Liston grew up in Homer, Alaska, where the forest came down into her backyard, and Roseburg, Oregon, where the Pacific Crest Trail meandered only about two hours from her home. She spent hours playing and hiding out in the woods and fell in love with the outdoors.

“My parents just would say ‘Go outside and play!’”

Her parents also inoculated in her the skills to get outside by taking Molly and her siblings skiing as early as three-years-old. For Molly, the outdoors is not just a hobby. She pursued a physical education degree with an outdoor adventure emphasis at the University of Alaska-Anchorage. In school, she began working with the current health, physical education and recreation director and associate professor, TJ Miller, running an outdoor program for student living on campus.

Molly now works at Pacific Northern Academy, an independent and non-sectarian private school in Anchorage, as the physical education teacher. It is Molly’s first steady job, but her desire for adventure cannot be tamed. In the summers she guides for Ascending Path or Chugach Adventures based out of Girdwood, Alaska. Molly also helps teach a few outdoor classes at UAA, including a beginning canoeing class that will be offered this summer. In her teaching Molly teaches her students that they can do anything.

“One of my major goals while teaching is to really empower students (both male and female) to try their best no matter where they begin physically or athletically… I encourage them to practice the things that they want to get better at and remind them that to be good at something it requires practice and repetition.”

Molly tries to be an inspiration to her students. She wants no one to ever feel as if they can’t do something for any reason.

“Another thing that I try to do is to simply be a positive role model. Most Physical Education teachers are the stereotypical athletic male and by being a strong athletic and female leader I hope to encourage those female students to break barriers in their own lives. It’s a very exciting and gratifying position to be in!”

Molly also works with college aged students at UAA. Molly’s experience landed her the job as an assistant professor for a 26-day expedition in the Brooks Range with UAA’s outdoor leadership program in 2014. The trip included hiking over 100 miles into the Brooks Range and rafting back out. There were nine students in the class, two were female.

Molly was the only female instructor so was left in a tent by herself, whereas everyone else had a tent mate, including the two other instructors who tented together.

“Yes, I felt very free because you are, you are really smelly and you just want your alone time so that was really nice, but I had to tear down my tent and set it up by myself every single day and cook all my own food. They all got to switch back and forth, so that was a little bit challenging.”

Molly is no stranger to working alone though. In 2012 she hiked the Oregon portion of the Pacific Crest Trail by herself. The journey started out as a trip between her brother Matt and her, but a week into the trip Matt couldn’t go any further due to injury. Molly, a capable outdoorswoman who is self reliant, wouldn’t let the idea of going alone stop her. She hiked about a month and over 500 miles by herself.

Molly and Matt had planned for such an occurrence knowing that he always gets hurt. He was nervous, but excited for Molly to continue. The two knew that she could make phone calls on her cell periodically when she had service and were confident in Molly’s abilities in the woods.

“We knew that it was going to be interesting, I mean, it’s tough, these things are still nerve wracking, but I’m not the first person to do that. There’s other women who hiked the whole thing by themselves.”

Despite the obvious dangers of being in the woods by yourself and of being a woman alone in the woods Molly found herself struggling with something much different than fears related to those dangers. Molly’s experience on the Pacific Crest Trail was a time of solitude and self reflection.

“You know it was really tough because there’s no route finding. When you have to route find you’re always thinking, you’re always like ‘okay I’m here,’ you’re looking at where you are on the map, but when you’re on the Pacific Crest Trail and you literally don’t have anything to think about other than yourself. It was very challenging – physically and mentally. I was really proud of myself. There was a lot of times I wanted to stop because of blisters or I don’t know maybe even being a little bit bored with myself because I’m such a social person. It was definitely very mentally challenging.”

While Molly battled with the isolation of the trail she finds the alone time to be one of the best parts of being outdoors.

“I just love how quiet it is when I’m by myself and just the freedom to be quiet by yourself, but then in the other aspect I love sharing the experiences with people.”

Alaska outdoor culture: Fostering women in the outdoors

Alaska boasted as the largest state in the union, with the largest mountain in North America and the greatest abundance of wildlife is truly a wild place. The inherent nature of Alaska inspires people to get outside. One look at Denali and it’s plain to see that getting outside is one of the best parts about visiting or living in Alaska. Alaska is an incredibly unique place that invites those who live here to go play outside.

With so much to offer in ways of outdoor activities there is a definite outdoor culture in the state of Alaska. Women who are often underrepresented in outdoor spheres are active members of the outdoor community in Alaska. No one is pushed away from being an adventurer in Alaska, where adventure still runs rampant and solitude can actually be found.

Monika Fleming, a University of Alaska Anchorage student originally from Chewelah, Washington came to Alaska after a slew of adventures that took her all the way to Nepal. Fleming found her home in the last frontier where there is a strong community of outdoorsy people.

“Pretty much every Alaskan I’ve met has done some stuff, like every single one of them, and some crazy stuff too. Even if they don’t do it all the time, the stuff they have done has been really kind of advanced,” said Fleming of Alaska’s outdoor culture. “I’m just like ‘Oh!’ …In the classes I’ve taken there’s this one girl Courtney, she’s the head of the sororities or something like that. She’s really hardy and outdoorsy, but she just looks like you know, just Alaskans always surprise you.”

However, Alaskans who’ve been here their whole lives don’t feel like they are doing anything out of the ordinary. Lifetime Alaskan Kendyl Murakami, who currently studies biology at UAA, is inspired by how there’s so much to do. Despite the cold she feels like it’s impossible to stay indoors living in Alaska.

“I feel like most of us when we grow up in Alaska we grow up with all this expertise surviving outside so I don’t feel like we [women] have any crazy limitations. We all know how to make a fire. We could chop down some wood or cut it in half or whatever, so there’s not a lot of restraints,” Murakami said of Alaskan women.

Not only is Alaska accepting of women getting outside it actually provides a community for it.

“If women, or men, doesn’t matter, if they really want to do something in the outdoors I think Alaska has a phenomenal community to foster that,” said Molly Liston a P.E. teacher at Pacific Northern Academy, a private non-sectarian school in Anchorage.

Pacific Northern Academy is just another example of Alaskan’s self reliant and adventurous way of life. The school’s mission is to “educate students to be exceptional learners and independent thinkers of vision, courage, and integrity.” Students at PNA are encouraged to play and be creative in their learning.

This self reliant attitude about education doesn’t end in the elementary and middle school of Pacific Northern Academy though. At UAA, an outdoor leadership program is offered to students via the health, physical education and recreation program. T.J. Miller the director of the program was Liston’s mentor when she went to college. Miller has lived in both Alaska and Colorado, working as a guide or outdoor instructor for the entirety of his life.

“You know I think up here, gosh, I see more mountain guides on Denali that are women than I saw in Colorado. I guess I would have to say it seems that Alaska has incorporated and embraced women a little more than other areas and I’m kind of comparing Alaska to Colorado, those are my two main states. And again maybe it’s social media, but I have seen more women in the industry doing well and excelling up here than other places.”

Regardless of what it is that makes Alaska such an outdoorsy place, one thing is for sure, there is no end to the possibilities of what one can explore. Undoubtedly there are thousands maybe even millions of untouched acres in the state just waiting to be explored and maybe a woman will be the next to conquer some astounding untouched outdoor feat in Alaska.